Beta City: Temporary, Collaborative City Design

Contents |

[edit] INTRODUCTION

“The Street is dead. That discovery has coincided with frantic attempts at its resuscitation…pedestrianisation intended to preserve - merely channels the flow of those doomed to destroy the object of their intended revereance with their feet.”[1]

For as long as man has built he has attempted to incarcerate himself in eternity, building with the mentality that structures will stand indefinitely.

…the quest for permanence, however, guides many of our choices. We want to achieve “lasting results” or find permanent solutions or enduring love, to make commitments, to invest our savings with permanent investment funds and to achieve sustainable regeneration. For most people the notion of permanence brings a sense of security and a hedge against risk and the winds of change.[2]

These desires are deep set into the human psyche, a reaction to our own comparatively short existence. Within the design of cities and architecture the notion of permanence is centuries old. Vitruvius wrote of “Firmitas”, a soundness in construction that today has come to constitute the notion of enduring presence:

“The thickness of the wall should, in my opinion, be such that armed men meeting on top of it may pass one another without interference. In the thickness there should be set a very close succession of ties made of charred olive wood, binding the two faces of the wall together like pins, to give it lasting endurance. For that is a material which neither decay, nor the weather, nor time can harm, but even though buried in the earth or set in the water it keeps sound and useful forever .And so not only city walls but substructures in general and all walls that require a thickness like that of a city wall, will be long (in failing to decay) if tied in this manner.”

However, accreted in layers over time their growth cities are continually in flux, shifting in aims and influenced by physical and socio-economic factors.

Today, city authorities seek to design for a permanent end-state condition, an approach that is increasingly outdated given the pace of modern urban life. In the UK planned new cities designed in the second half of the twentieth century, such as Craigavon, were intended as a permanent vision of a new method of urban planning and modern means of life, but subjected to the real world of political uncertainty and post-industrial decline they remain a powerful reminder of the impossibility of permanence.

[edit] ORIGINS

The Western World experienced a decline in primary and secondary industries in the late 20th century. Compounded by the suburbanisation of city edges and the creation of out-of-town shopping centres that has de-stabilised the city centre. No longer the place of commerce and exchange, the once thriving shopping units and industrial areas now lie empty.

There is growing uncertainty about the future, exacerbated by the increasing “freak” occurrence of natural disasters and the global financial recession that has shattered the belief in perpetual economic growth; with a mass over-speculation undermining an economic system that was thought by many to be a permanent “endstate” model of economic development. With this has come a loss of faith in “big” thinking and governmental authority.

The city of Belfast embodies many of these factors. Once a thriving industrial city based on linen export and shipbuilding, it had a prosperous city centre with shops selling luxury products as well as locally produced goods. However the demise in shipbuilding and foreign competition for the linen trade withered the economic power of the city, reducing expendable incomes and ultimately bringing about the closure of many stores in the city centre. The once iconic Anderson & McAuley's, which opened in 1861 finally closed in 1994, ending a legacy of local traders in Belfast, a layer of the city’s past that has been now replaced with global brands such as Zara, Burger-King and Footlocker.[4]

The austerity of the recession and the influence of shopping centres also played a significant role in the destabilisation of the city centre. The completion of Victoria Square, a large high-end shopping centre attracted retailers and footfall away from the historic high street of Donegall Place, and the perceived centre of the city. Such a shift has had a profound effect on the city’s socio-economic structure. The city centre is no longer the product of local industries, there is no longer a vibrant mix of shops along Donegall place. Instead a bargain, low-cost monoculture has developed, with globalised brands and vacant lots as local businesses collapse.[5]

This has had a prfound impact on the city’s economy. The traditional central location once attracted the highest rent values, indicating a quality and economic advantage to the location. Units on Dongeall square once retailed at 275 pounds per square foot, but today are available for 150 pounds per square foot. Conversely streets around the new centre have increased their unit value from 35 pounds per square foot in the late 1990’s to around 130 pounds today. Now more than ever landlords are seeking short-term, real-time solutions to prevent any further decay of the city centre. [6]

In the past twenty years we have also seen a change in our means of life. The once stiff-collared 9-5 lifestyle is now becoming a more integrated live/work way of life, allowing people to work from home, have condensed weeks or tap into the office through the Internet as they travel. This all has a fundamental impact on the morphology of cities once designed to cater for the mass of people who commute into and work in city centres.

In 2009 12.8 per cent of the population of the UK worked from home [7], with offices regularly only filling 50 percent of their desk space. Such a spatial and temporal shift in the structure of our lives will soon begin to manifest itself in the morphology of our environment.

The impact of technology has probably been the most significant shift in the way we live today. No longer separated by time or distance we live in a global network, with the Internet facilitating and cultivating an ecosystem of online users who openly move and contribute to the network, and whose movements are tracked, mapped and analysed to further develop the system. Moreover with the advancements in mobile technology we can be connected on the move. The sociologist Zygmunt Bauman spoke of this less anchored reality in Liquid Modernity. In this Bauman makes the connection between solidity and permanence, and elaborates and contextualises Marx’s communist manifesto “...all that is solid Melts into air”

The 'melting of solids', the permanent feature of modernity, has therefore acquired a new meaning, and above all has been redirected to a new target - the effects of that redirection being the dissolution of forces which could keep the question of order and system on the political agenda. The solids are the bonds which interlock individual choices in collective projects and actions - the patterns of communication and co-ordination between individually conducted life policies on the one hand and political actions of human collectivities on the other.

Such uncertainty and shifts in our lifestyles has led to a counter-culture of activism, those without faith in what they see as a failing late-capitalist system taking to the streets to voice their opinion and make a change in real time and space. This mentality is best observed in the recent Occupy movements that occurred in Liberty plaza with Occupy Wall Street and Occupy London's occupation of St. Paul's Cathedral in 2012.

“... tens of thousands gathered to commemorate the two-month anniversary of Occupy Wall Street. They filled the Financial District. They occupied the subways. They held mass rallies at Union Square and Foley Square, then filed across the Brooklyn Bridge, beneath “bat-signal” messages projected on the side of the Verizon Building: “This is the beginning of the beginning.”

Moving between the physical and the virtual, participants navigated a hypercity built of granite and asphalt, algorithms and information, appropriating its platforms and creating new structures within it. They posted links, updates, photos and videos on social media sites; deliberated in chat rooms and collaborated on crowdmaps; as they took to the streets with smartphones.

These movements also tap into the various dimensions we now occupy, both physical and digital, in order to organise and activate/hacktivate city spaces, using social networks such as Facebook to organise their meetings and activities, and using Twitter to post and contact their specific audience group. Additionally their continued activity, along with the political replies builds an urban fabric which not only creatively re-imagines the public realm, but also shows the frailties of the current political and economic system, where governments grappling for control resort to brute force to remove and silence the majority. What it suggests is that we are moving away from late modernist paradigms of hierarchical control and towards a growth pattern that is succeptible to change. We are beginning to see the city as a volatile platform for interaction, a Beta city philosophy, a state of continual change.

[edit] CASE STUDIES

Some examples of this philosophy are described in the following section. As examples from the UK they show how such an approach to the design of cities can be applied within a British context, moreover at a variety of scales they show that it is not a specific form of masterplanning, but a means of thinking about urban space that can be applied at a variety of scales.

[edit] Incredible Edible Todmorden

A movement created in the Lancashire town of Todmorden by a coalition of residents who had grown tired of established policies and procedures for handling of the public realm, they decided to take control of their spaces directly. The movement began with guerrilla gardening activities in public spaces, planting edible fruits and vegetables, creating discussion and progress through action:

‘You just need to understand how we all tick. And we’re all the same. We’re bored to death and cynical about strategies and policies and rhetoric. But what we like is action, we like to get involved in things and we like things to point at.’

Their actions did not go unnoticed by local authorties, along with public and private sector landowners, who quickly became supportive of the scheme, providing public places, schools, train-stations and car parks, for the planting of fruit trees. The core objective of the scheme is to create civic pride in the residents of the town, generating further support and reducing “nimby-ism”, creating pathways for increased and more open discussions with residents about ideas for development in the town; whilst simultaneously building a sustainable local economy through reduced rates of vandalism, increased passive surveillance and sales from the produce of edible landscapes.

In this example it is not the professions concerned with the built environment affecting change, rather residents who have grown tired of urban renewal based on the canon of professional thinking. Instead, the minority have implemented a positive behavioural change in the town, not by physical constructions but simple, direct adaptations and re-imaginations of existing public space.

[edit] Forum for Alternative Belfast

Setup in 2009 by Belfast architects Declan Hill and Mark Hackett, FAB is a non-profit organisation that “campaigns for a better and a more equitable built environment in Belfast.” To do this they consider themselves as both a think and do-tank that will counter the unconstrained speculative development that has been responsible for urban decline in the inner city. By holding summer and winter schools and exhibitions and by producing publications, they encourage experienced practitioners, students and residents of the areas in which they are working to contribute to discussions and ongoing work to reconsider the possibilities of the post-conflict fabric of Belfast.

FAB establishes a platform in the city for discussion, to create interest and activity, not through technological or guerrilla activities but by continually tapping into the experience of skilled and passionate planners, architects and developers, continuously publishing online, advertising in the city, exhibiting in local architecture centres, and remaining in the public consciousness via the radio and newspapers.

Recently their contribution to the Venice Biennale was an attempt to highlight the urban plight of Belfast to a global community, using the “Missing Map” a part of their ongoing research into the city, they showed that over 35% of the inner city lies vacant. Within their summer schools they also provide potential solutions and re-imaginations of these spaces, with projects such as the Bank Square scheme that reinterprets one of Belfast’s existing vacant spaces and by subtly teasing out the identity of the space, they begin to create a place in Belfast of true public character. Additionally their fight against the infrastructure that has been used as a segregating barrier in the city between conflicting communities has seen them develop proposals for the integration of motorways into the fabric of the city, creating new flows in urban space and re-humanising areas of the city long lost to the car.

[edit] Muf Architects.

The work of Muf architects extends much further than the perceived notions of an architectural practice. In so far as possible they work to include the voice of others; a practice engrained in “mutual knowledge', and the context of the public realm indicat(ing) a social (spatial) ambition beyond the fixity of the building as object.”[13] This also leads to the production of much more than just physical constructions, they treat design of urban space as a negotiation between spatial arrangements and material resolutions “that come about through consultation between public and private, communal and individual”[14] The inclusivity of this design process, fused with Muf’s role as design leaders allows them to thread lines between corporate developers, local residents and government officials, creating often unexpected outcomes.

One such example of this is their recent work in Dalston, London. A work that was “driven by observation, conversation and testing on the ground. It (began) with the identification and celebration of existing assets, social cultural and physical.” Which formed the basis of a collaborative, bottom-up masterplan for the area.

A strategy of design moves and cultural activity was devised to enhance the public realm for both residents and the everyday needs of residents; valuing the existing, nurturing all possibilities and defining what is missing. What originates from this is not architecture or urbanism in a conventional sense, but a manifesto that is embodied in a framework strategy for the area. The interventions into the urban fabric too are of a less architecturally permanent state. By creating places such as the guerrilla gardens of Dalston Lane, the creation of “Host Spaces” to deepen the culture of Dalston, or the Release spaces of Winchester Place, they engage with the city on a more transient, light-footed manner, but unlike permanent approaches they are also engrained into the rhythms and needs of everyday life in Dalston; intervening and improving the quality of space within a short timeframe.

[edit] PROS AND CONS

Much of what has been described above involves integrated participation of the designers and activists; those responsible for design behaving like glue between the parties involved to achieve a common goal. This is contrary to the traditional image of an architect-centred design process, making decisions from the top of a hierarchical structure in isolation. To many practicing professionals this may be a concern, with the influx of “laypersons” into the process degrading the profession from a respected institution to a public forum.

In writing the article “Against Kickstarter Urbanism” Alexandra Lange confronts this issue directly. Being an open-sourced “funding platform for creative projects”[15] Kickstarter taps into the power of the internet to gather attention and attract funding from online participants. Originally intended for product design it was never considered as a tool in open-sourcing the public realm, and within that emerged a critical flaw:

“You can’t Kickstart affordable housing, but the really cool tent for the discussion thereof. Gizmo is close to gimmick, and worthy goals have to be dressed up in complex geometries for Kickstarter.”[16]

Using an online website makes it difficult to address serious urban topics that will make real change to a place, too often it is the “money-shots” that attract attention to a scheme which may not have the richness or appropriateness of a more subtle, less enthralling strategy. The lowline in New-York is an example of such criticism, which seeks to reuse an underground tram network to create a public park-like space, a grand vision, but a massive gamble in the public realm. The fundamental risk is that those without a comprehensive understanding of the built environment could affect detrimental changes to our cities; seduced by high resolution renders and persuasive video presentations to create instant gains and short-term success, but never fostering a sense of meaningful place making.

However an integrated engagement with the public can also have positive outcomes on the built environment. In the example of Peter Zumthor’s recent gateway proposal for Isny it was the population who rejected the scheme.[17] Such openness and transparency of process can establish channels for greater dialogue between professionals and populations, generating greater involvement and the potential for a more meaningful, representative outcome. At a time when decisions regarding cities are made by teams, committees, commissions and panels this gives the individual some hope that they can make a contribution to their immediate world and its physical representation.

This division between decision makers and the wider city also creates a divide between the philosophy of the decision makers and that of a city. “...Plans are often outdated before they are published...perpetuat(ing) categories of use that are inflexible and unsuited to times of continuous change.”[18] In planning for an ultimate condition they overlook the fact that a city, often through necessity, is continually evolving in order to stay relevant, remain competitive and provide for its population.

Firmitas, meaning strong, firm, steadfast has been extrapolated today to refer to permanence; however referring to it in its original context it is possible to have a temporary firmitas, a soundness of construction that is not intended to be permanent in one location or incarnation, but when constructed creates a sense of architectural delight to satisfy Vitruivan principles. Many forms of Filigree construction satisfy this for example, and are also more ecologically resolute through reduced material consumption.

When we speak of a building, or city, and speak of permanence we speak of more than just material strength. Irrespective of its incarnation, a beautifully crafted, coveted and required solution to an urban need will outlive any physical manifestation of material. Over time the material will change, but the intent that it originally embodied will remain; altered, adapted, moved or rebuilt; permanent in the city, but impermanent in construction, dynamic as opposed to static.

[edit] SUMMARY/CONCLUSION

If urban thinking continues along its current path the result will be evermore cities, with evermore generic conditions, a repetition of form set within a late modernist paradigm, an obsession with order and formal gestures; unable to fully represent the complexities and multiplicities of our daily lives. Our current “professional” approach all too often creates sedated spaces, passive and neutral; a possible alternative may lie in adapting a collaborative, integrated approach. By handing the city back to the will of the public the urban fabric will adapt, becoming representative of the conditions of place and more meaningful to both residents and the urban fabric of a city. By no means does this make the process easier or more streamlined, it will remain a complex, messy and at times conflict-laden endeavour; however it will gain relevance, and become more representative of the everyday situations and rhythms of an urban space.

Cities are places of continuous change and in themselves are a reflection of the cultures and forces that shape them, there can be no endstate. The means for future approaches should better aim to represent this condition. An approach that could produce tangible results within short-timeframes. As we live in an increasingly multi-dimensional era so too should our urban fabric, no longer resigned as physical artefacts in the real world, but networked and meshed into the web of contemporary living.

This Article was created by --Shmg 22:10, 11 December 2012 (UTC)

[edit] Related articles on Designing Buildings Wiki

- Architectural styles.

- Consultation process.

- Do it together architecture.

- Localism act.

- Masterplanning

- Neighbourhood planning.

- Smart cities.

- Speculative architecture.

[edit] External references

- [1] R.Koolhaas, B. Mau, Generic City, S,M,L,XL, 1995 p.1253

- [2] P.Bishop and L.Williams . Temporary City, Routledge, 2012 P.11

- [3] Vitruvius Pollio, and M. H. Morgan. 1960. Vitruvius : The ten books on architecture [De architectura.], Book I, Chap. 5.3

- [4] C.Weir and M.Canning, Is Belfast still the place to be for retailers? Belfast Telegraph (accessed 06 November 2012)

- [5] Ibid

- [6] Ibid

- [7] T.Dwelly, A.Lake, and L.Thomson, Workhubs: Smart Workspaces for the Low Carbon Economy, 2010, www.ruralsussex.org.uk/assets/assets/HHB-Workhubsfinal report2010%20part1.pdf (accessed 07 November 2012)

- [8]K. Marx and F.Engels, The Communist Manifesto, 1888 p.6

- [9] Z.Bauman. Liquid Modernity. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, 2006, pg.6

- [10] J.Massey and B.Snyder. Occupying Wall Street: Spaces and Places of Political Action.

- [11] ibid

- [12] 00:/, Compendium for the civic economy, 00:/,2011 p.89

- [13] J.Till, T.Schneider and N.Awan, Spatial Agency: Other Ways of Doing Architecture http://www.spatialagency.net/database/muf (Accessed 4- December 2012)

- [14] ibid

- [15] http://www.kickstarter.com/ (Accessed 28 November 2012)

- [16] A.Lange, Against Kickstarter Urbaninsm.

- [17] K.Rosenfield Majority rules against Zumthor’s “Glass Underpants” in Isny, http://www.archdaily.com/208941/majority-rules-against-zumthor%E2%80%99s-%E2%80%9Cglass-underpants%E2%80%9D-in-isny/ 2012 (Accessed 16 November 2012)

- [18]P.Bishop and L.Williams 2012. Temporary City, Routledge p.19

- [19] J.Kaliski, The Present City and the Practice of City Design, in Everyday Urbanism, J. Chase, M. Crawford, and J. Kaliski, Editors. 1999, The Monacelli Press, Inc.: New York. p

- [20] R.Arnheim [1904-]. 1977. Thoughts on durability: Architecture as an affirmation of confidence. AIA Journal 66, (7): 48-50.

Featured articles and news

How can digital twins boost profitability within construction?

A brief description of a smart construction dashboard, collecting as-built data, as a s site changes forming an accurate digital twin.

Unlocking surplus public defence land and more to speed up the delivery of housing.

The Planning and Infrastructure bill oulined

With reactions from IHBC and others on its potential impacts.

Farnborough College Unveils its Half-house for Sustainable Construction Training.

Spring Statement 2025 with reactions from industry

Confirming previously announced funding, and welfare changes amid adjusted growth forecast.

Scottish Government responds to Grenfell report

As fund for unsafe cladding assessments is launched.

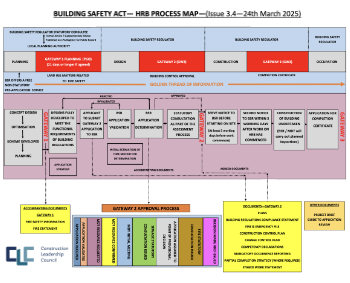

CLC and BSR process map for HRB approvals

One of the initial outputs of their weekly BSR meetings.

Architects Academy at an insulation manufacturing facility

Programme of technical engagement for aspiring designers.

Building Safety Levy technical consultation response

Details of the planned levy now due in 2026.

Great British Energy install solar on school and NHS sites

200 schools and 200 NHS sites to get solar systems, as first project of the newly formed government initiative.

600 million for 60,000 more skilled construction workers

Announced by Treasury ahead of the Spring Statement.

The restoration of the novelist’s birthplace in Eastwood.

Life Critical Fire Safety External Wall System LCFS EWS

Breaking down what is meant by this now often used term.

PAC report on the Remediation of Dangerous Cladding

Recommendations on workforce, transparency, support, insurance, funding, fraud and mismanagement.

New towns, expanded settlements and housing delivery

Modular inquiry asks if new towns and expanded settlements are an effective means of delivering housing.

Building Engineering Business Survey Q1 2025

Survey shows growth remains flat as skill shortages and volatile pricing persist.

Comments

To start a discussion about this article, click 'Add a comment' above and add your thoughts to this discussion page.